These whispers were far from Theoderic’s mind in 519. All was in order and all was prepared for an orderly succession and a long and glorious future.

Then Eutharic died unexpectedly in 522 or 523, and without the crucial certainty of succession, the world Theoderic had brought together began to come undone.

Civility and toleration

Civility and toleration were the hallmarks of Theoderic’s rule in Italy—he said as much himself. If they were the civility and toleration we find in strong-armed imperial orders, they were still real, but they were not the whole of his regime, nor was his regime the whole of life in Italy. To do jus¬tice to him and to understand what was lost when his successors destroyed what he had built, we have to slow down and marvel at how life went on in his land and time.

Theoderic was not merely lucky. A good reputation follows those who are well spoken of by their contemporaries, especially when they make sure to have contemporaries speak well of them. Then a measure of luck takes over. People wrote books by hand on papyrus or animal skins, and they were copied a few dozen times at most, passed from hand to hand, and preserved in households of the wealthy and powerful—and therefore of the doomed. From no age of antiquity do more than a tiny fraction of the books written survive to us in even one medieval copy kukeri carnival.

Yet we have nearly 150 letters from Theoderic’s time that profess to be from his own hand, and come at least from the hands of those who served his will and heeded it most closely; we have transcripts of synods of the church that met under his direction; we have almost 300 letters from En- nodius of Pavia, the churchman with ambitions, who also wrote a grandi¬ose panegyric oration in Theoderic’s honor, to sing his praises to his face and the faces of his court, and poems and other documents besides; we have letters from every pope who reigned in his time; we have the Book of Pontiffs recounting the deeds of those popes in short compass (and also the crucial part of the variant edition of that book done by the followers of the would-be pope Laurentius); we have the philosophical, theological, and au¬tobiographical writings of Boethius; we have other fragments of panegyric orations in honor of his court, the chronicle of all the years of Rome made in honor of Eutharic, and a history of the Goths that was put together in Constantinople twenty-five years after he died but that depended somehow on the propaganda and learning of Theoderic’s last years. Considering the devastation that would strike his Italy in the decades after his death, and the long history of political disunity and disarray that would follow, the survival of so many books and artifacts of his time is a testimony to the ambitions of the man and to his posthumous good fortune.

Uppsala Gothic Bible

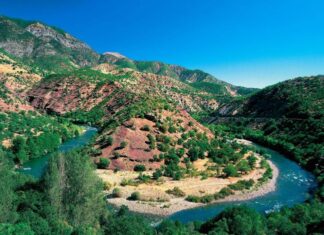

Other books survive to represent his court and its tastes: the Uppsala Gothic Bible has an obvious claim to our attention, but no less impressive is the elaborate and expensive manuscript, also coming from Ravenna and perhaps from the same book-producing house, of the Corpus Agrimensorum—the Collection of Surveyors. Magnificently illustrated, this manuscript brought together the technical treatises of the men who made possible Roman property management and Roman imperialism, the surveyors who put names and measures on the land and regulated a world of agricultural property for the benefit of the imperialists and their favorites. At approximately the same time, scholars at Theoderic’s court wrote about geography as well, and in the seventh century an anonymous writer admired Latin writers of this period for their learning, authors with the seemingly Gothic names Athanarid, Eldevald, and Marcomir Theoderic and notionally alongside.

Theoderic once had to settle a property dispute that called on the surveyors’ skills. The Chaldeans, he reminded his subjects, had discovered geometry, but it was the Egyptians who put it to practical use by marking out the lands that the Nile flooded each year. Augustus himself had, after all, ordered that the whole Roman world be surveyed and recorded in a census. “Today,” Theoderic said, “the surveyor’s art is far more popular than the other numerical sciences. Arithmetic has empty classrooms, geometry is for specialists only, astronomy and music offer knowledge for knowledge’s sake only. But the surveyors are the wizards who bring peace among men. You might think them crazed when you see them prowling the woodland in search of boundary markers, for the road is their book and they read it well.”7 Theoderic was every bit the Roman ruler in his patronage of these books and related arts.